Long before Adi Maulana could explain the mechanics of tectonic shifts or the chemical mysteries of rare earth minerals, he was a boy who simply could not walk past a stone without picking it up.

He would turn the rock in his hand, weighing it, staring at its colors and cracks as if it held a secret he could almost grasp — but not yet.

"I remember wondering," he said recently, sitting in his office filled with maps and mineral samples, "how could something so small carry such an ancient story?"

It is a curiosity that has never left him.

Born on April 28, 1980, Maulana grew up in Balikpapan, a coastal city where the land seems in constant negotiation with the sea. His fascination with the earth was instinctive, a quiet magnetism that later found a name: geology.

READ: The Hidden Power Beneath Sulawesi: How Banggai’s Rare Earths Could Change the Global Game

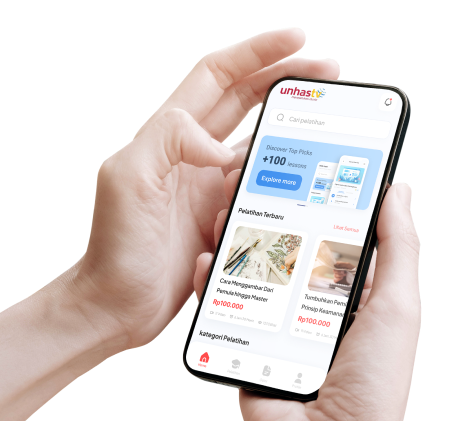

In 1997, he enrolled at Hasanuddin University, not just to learn about rocks and faults, but to understand the planet’s secret language.

University life was not easy.

The coursework was grueling, the fieldwork grittier than the textbooks suggested. Days were spent under punishing sun or pouring rain, hiking across remote hills to take measurements few would ever read.

"It taught me that the earth does not give up her secrets easily," he said, laughing softly. "You have to earn them."

He rose to lead the student geology association, not because he sought attention, but because he believed knowledge was meant to be shared — and challenged.

Still, Makassar was only the beginning. Maulana understood early that staying put was not an option.

He went abroad — first to Australia, then Japan, then the United States — in search of broader horizons and harder questions.

In Fukuoka, at Kyushu University, he buried himself in the study of petrology and geochemistry, disciplines so niche that few beyond academic circles could pronounce them. Yet to him, each isotope and mineral formation was a new sentence in the Earth’s ancient diary.

"It humbled me," he said. "The more you know, the more you realize how little you understand."

Along the way, there were failures — exams not passed on the first attempt, research proposals rejected without explanation, loneliness that crept into long winters abroad.

There were moments when he questioned the path he had chosen, whether the pursuit of understanding was worth the solitude it demanded.

"But even when I was at my lowest," he said, "I never stopped believing the answers were out there. Somewhere."

Carl Sagan’s words, etched into his mind, often echoed: "Somewhere, something incredible is waiting to be known."

In America, he joined the prestigious International Visitor Leadership Program, stepping into rooms with scientists, policymakers, and entrepreneurs. They spoke of sustainable mining, environmental stewardship, the ethics of resource extraction — and Maulana listened, absorbing, questioning, challenging.

One evening, after a long round of meetings in Washington, he sat by the Potomac River alone, notebook on his lap, trying to capture what it all meant.

"We are stewards," he scribbled. "Not owners."

Eventually, he returned home. Not because Indonesia was easy, but because it was necessary.

The island nation, stretched thin across fault lines and volcanic arcs, held more questions than most scientists could ever hope to answer. And it needed more voices like his.

At Hasanuddin University, he became a professor. Later, Vice Rector. Titles he wears lightly. "I’m still a student," he insisted. "The earth keeps teaching."

One of his missions today is to unlock Indonesia’s potential in rare earth minerals — essential ingredients for smartphones, wind turbines, and electric vehicles. For decades, the country sat atop these treasures without fully understanding their worth.

Maulana’s research is changing that. He has mapped veins of critical minerals across Sulawesi and beyond, advocating for a smarter, more sustainable strategy — one where Indonesia no longer merely exports raw materials, but becomes a true player in the global high-tech economy.

But nature is not easily tamed.

When a 7.5-magnitude earthquake devastated Palu in 2018, Maulana was one of the first scientists on national television, explaining the furious dance of tectonic plates, the unseen fractures that had snapped without warning.

He spoke calmly, precisely. But inside, he mourned. "For every life lost," he said, "there is a story that will never be told."

He does not romanticize disaster.

Instead, he sees in every fault line a conversation — between what is known and what remains mysterious.

Each shift in the earth’s crust reminds him: stability is an illusion. "Maybe that’s why I never feel finished," he said. "Science keeps moving. So must we."

Today, Maulana’s days are filled with meetings about innovation hubs, partnerships with industries, workshops for students. But he still carves out time for the field, for the messy, uncertain business of discovery.

He mentors young geologists, urging them not to memorize facts, but to ask better questions. And when he speaks to them, he often returns to a simple image: a boy holding a stone, wondering what secrets it holds.

"I tell them," he said, smiling, "never stop picking up rocks."

The earth, he believes, still has more to say. And he, still listening, is determined to hear it.

_6-300x201.webp)

_1-300x162.webp)